|

| (c) Taryn Simon |

Taryn Simon, Paperwork and the Will of the Capital is

on view at

Gagosian Gallery

555 West 24th Street

February 18 - March 26, 2016

Throughout much of her artistic

career, Taryn Simon (b. 1975) has utilized the power of visual media—including

photography, sculpture, video, and performance—to critique systems of power. Her

work exposes the dark side of existing practices and, in particular, the ways in

which law affects the lives of people. Simon exploits the dual record-keeping

and fiction-making role of photography to document and fabricate the invisible.

For example, in The Innocents series

(2003), the artist shames the flawed American criminal justice system by

photographing wrongfully convicted men at the sites of their alleged crimes. Such

works reveal the inadequacies or, more often, harms that result from the

current systems in place. Her works compel the question: whom are these laws meant

to serve?

Simon’s

work answers that the law is meant to serve its people, but the practical applications

of law often do not reflect this purpose.

Law exists to maintain order that will facilitate a free society in

which people can pursue happiness without impinging upon the pursuits of

others. However, law is often used against the very people it was meant to serve

and protect.

|

| (c) Taryn Simon |

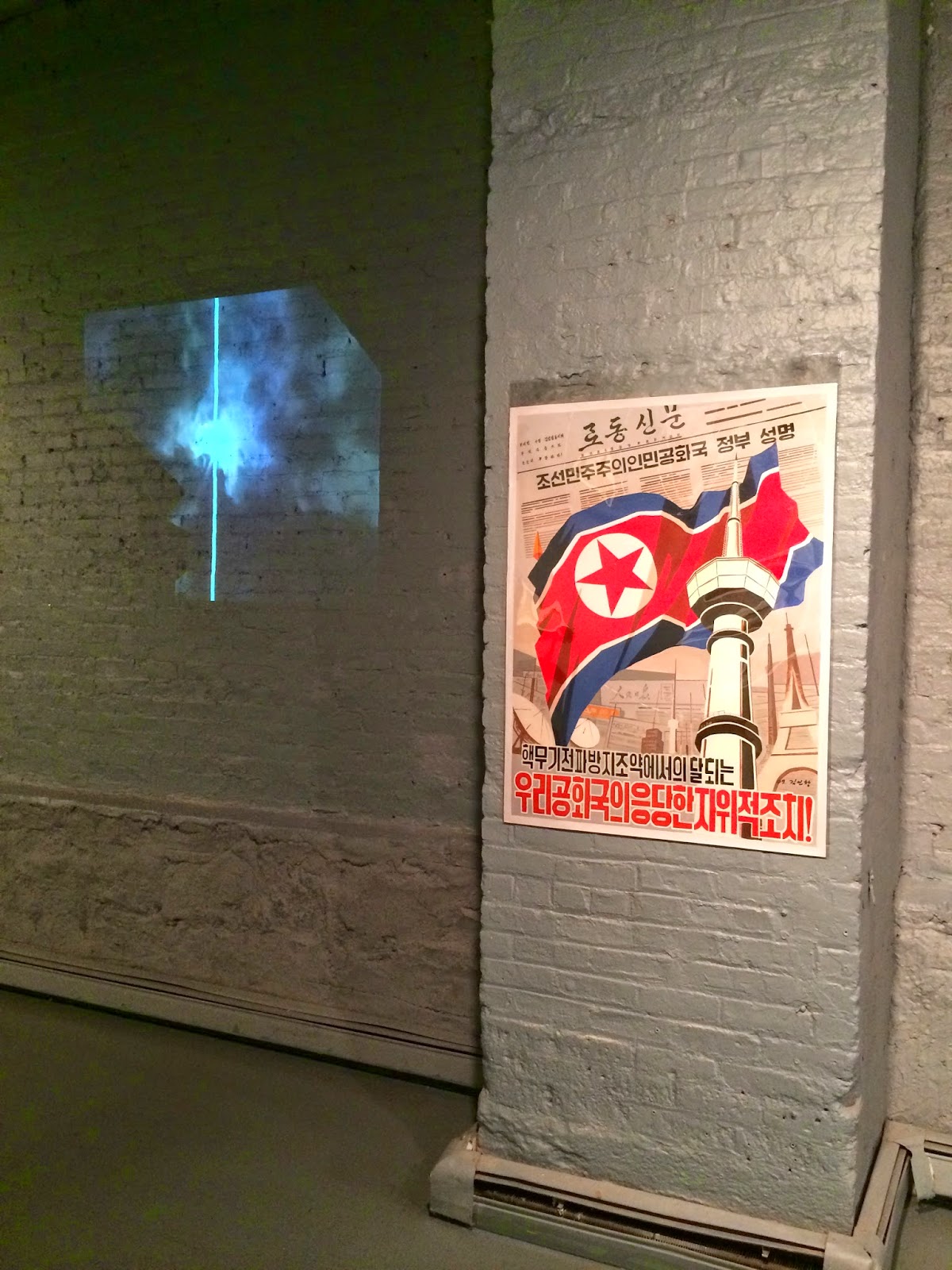

If

Simon’s previous work exposed the perverse applications of law, her most recent

body of works on display at Gagosian Gallery reveals another side of law: its

empty and symbolic nature. Part humor, part lament, we often joke that politicians

are full of crap. Unfortunately, the statement is funny because it is often

true. Simon’s photographs and sculptures highlight the artificiality and

hopelessly symbolic nature of international treaties: perhaps some of the

emptiest promises by one group of politicians to another.

The

power of these works—the large photographs in particular—stems from captivating

images that, despite their startling vividness, remain harmless to the viewer.

We use flowers

as harmless speech. We buy flowers most often as symbolic gestures to

commemorate an occasion or to express particular sentiments to others. We use

flowers as harmless objects of contemplation, to provide visual reminders of

such sentiments and occasions.

Such speech-flowers

are fragile and ephemeral. Their visual and olfactory pleasures expire as

quickly as the feelings of the occasion begin to fade from our memories. When

they lose their value as sensory pleasure-givers, we toss them out. Unlike

other symbolic gifts, we readily dispose of flowers because of their purpose as

temporary symbols.[*]

|

| (c) Taryn Simon |

Simon

highlights the utterly symbolic and superficial role of flowers—and the

occasions they were to commemorate—by exaggerating the surface beauty of

flowers that were once sitting on the tables where international powers signed various

agreements. Most of the photographs show exquisite arrangements in intensely vivid

colors, all against equally striking and beautifully color-blocked backgrounds.

However, the texts accompanying the mesmerizing centerpieces state the common

fate of all these treaties: failure of the signatories to implement them.

The artist

thereby disturbs the easy assumptions held by many people, that once codified

into law, the harms addressed by the law will remedy themselves. Her beautiful

photos and their accompanying texts expose this as a faulty assumption, which presumes

the automatic integration of such agreements into real life. However, laws do

not execute themselves—people do.

First,

many international treaties are not self-executing; local governments must pass

laws that allow their execution. Even after the agreements are passed as local

laws, law truly exists—and therefore holds power—when it is enforced in

everyday life. Without enforcement, these international agreements remain as

mere words on paper, nice and fanciful ideas, and nice gestures by participating

governments, yet nothing more.

The

horror bestowed upon us by Simon’s beautiful work stems from the realization

that this is actually how legal systems in general work, and that substantial

harm can result from the nature of law as a multi-step process. A law may be

passed because of a felt need to address existing problems, but the law can

only fulfill its initial purpose when it is executed properly in everyday life,

down to the police men, government agencies, and the judiciary.

|

| (c) Taryn Simon |

Today, when instances

of misapplication and faulty enforcement of the law continue to demonstrate the

shortcomings of the current system, Simon’s recent work prompts a second look

at law as “mere words,” and invites us to emancipate it from its purely

symbolic status toward a working system that better serves its true master: the

people.

[*] The other side of this sad fate of flowers as symbols

is that if one does not wish their flowers to meet their inevitable destiny in

the trash, one must prematurely remove them from their life-extending

environments in water and place them between the pages of a book—or a

flower-press, as Simon has—and crush them live in the name of preservation.