|

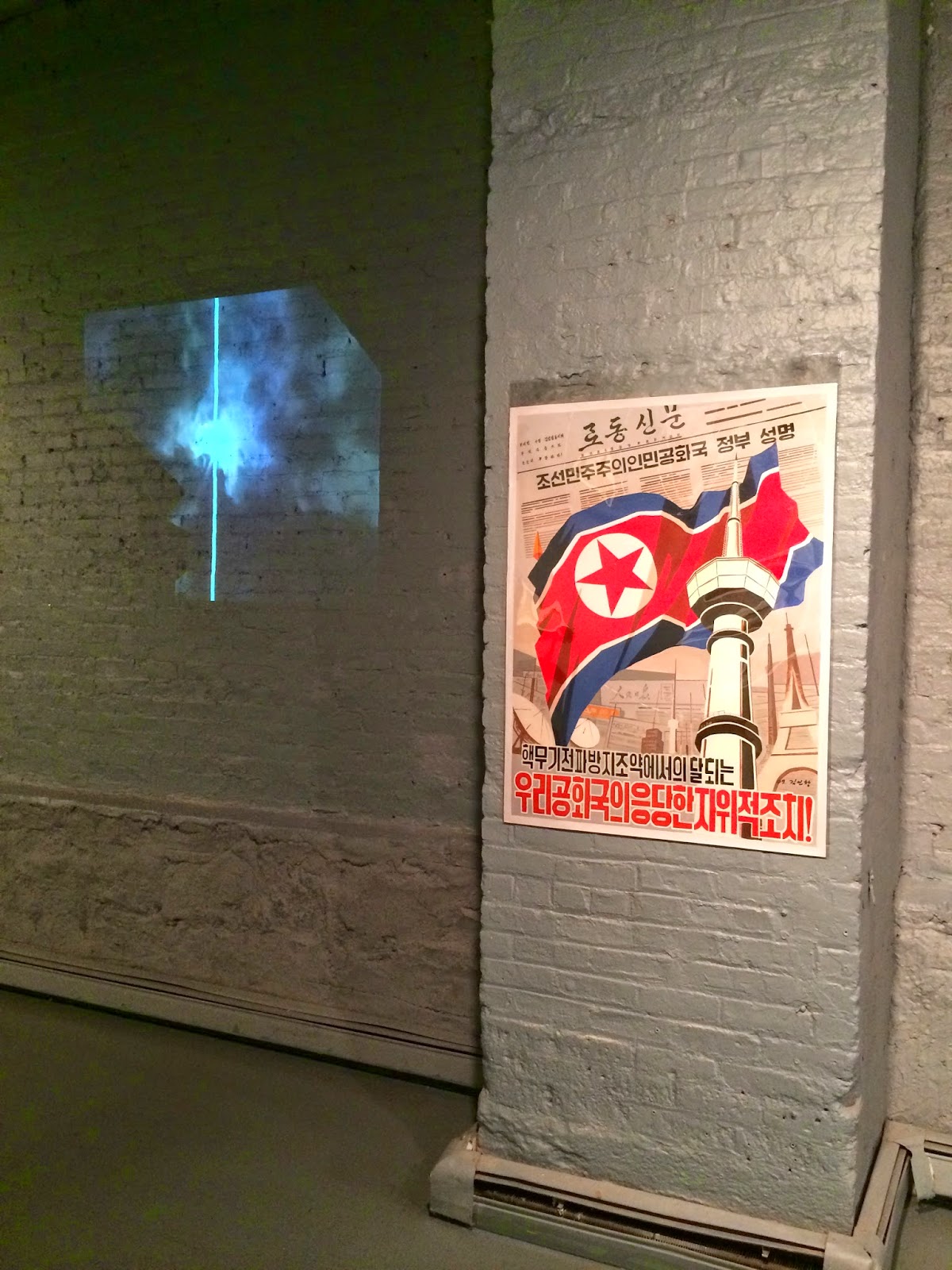

| View of Yooah Park's Music Box series (2013) and North Korean posters (from left to right) by Kim In Chang and Ji Jeong Sik. |

“KOREA” at FiveMyles Gallery

558 St. John’s Place

Brooklyn, NYC

June 25 – July 13, 2014

The

exhibition simply titled “KOREA,” curated by Han Heng-Gil, is a rare occasion,

if not the first here, that has provided an opportunity for New Yorkers to view

contemporary works by North and South Korean artists within the same space. Mr.

Han has been around the New York City art scene as a curator at The Jamaica

Center for Arts & Learning and, over the years, has developed relationships

with Korean artists who have both passed through the cultural hub for brief

residencies as well as those who have decided to stick around for a longer term.

Han occasionally travels back and forth to NYC and South Korea, but the current

exhibition at FiveMyles Gallery in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, is the result of a

trip the curator recently made to North Korea. He was fortunate to have been

able to bring back several paintings by North Korean artists, whose work are on

display with those of South Korean as well as Korean American artists.

Whenever

I see an art exhibit as of late, my focus increasingly turns to the curatorial

efforts: the way in which the selected art works are displayed as a whole,

their flow as overcoming and complicating what the individual works may offer

in isolated or otherwise different contexts. Sometimes a curator makes or

breaks art works by their arrangements in a given space. My interest in “KOREA”

lies in the clear traces of the curator’s hand. When visitors walk into the

gallery, the visual divide between the two sides of the space is clear: the two

dimensional works along the left side of the space are monochrome, while the

works along the right side burst in a clash of vivid colors. In the middle of

the floor between the two divides, bronze busts of the former president of

South Korea, Lee Myung Bak, and the likewise former ruler of North Korea, Kim

Jong-Il, turn around on the floor—just moving in for, or breaking away from, a

kiss.

The

bronze work, titled Me and You, You and Me, 2011, is by SunTek Chung, a born-and-raised American. Its position at

the center of the space casts a curious light on the nature of the entire show

itself: was this convergence of North and South Korean art work—and a critique

of North-South relations—only possible by virtue of its locale in New York

City, a third-party? NYC serves as the neutral ground (arguably the DMZ in this

context) in which the curator (also a “global” citizen in a sense, though South

Korean by nationality) is able to articulate a possible utopia or instigate a dialogue

about the relationship between two nations whose separation, Mr. Han seems to

suggest, have been imposed—and still exist—artificially.

The

installation of the art works indicates the artificiality of the divide between

North and South (similarly applicable to East and West, but that is indeed

another discussion à la Edward Said). The

monochrome side of the exhibit is particularly interesting especially in

context of the recent Korean monochrome “trend” as legitimized by exhibitions in

“Western” spaces (Alexander Gray Associates in NYC, for one) and the climbing

prices for such representative mid- and late-career artists such as (now

Guggenheim veteran) Lee Ufan and Park Seo-bo. In contrast, perhaps the nearly

intrusive vividness of bright colors on the right side of the gallery may even

appear too cheesy and “pop.”

|

| View of the left side of the gallery, including works by Pang In Soo, Kim Tcha Sup, Choi Gye Keun, Choi Il Dan, and Ri Chang. |

“KOREA,”

however, does not clearly indicate which of the works are by North, South, or

Korean American artists. The majestically tacit North Korean monochrome ink

paintings hang next to South Korean ones, whereas the display of colorful North

Korean propaganda posters from 2007 are interspersed by the equally (if not

more) colorful paintings by New York-based Yooah Park and a projection of Cheonggyecheon Medley (2011) by Kelvin

Kyung Kun Park, a UCLA and CalArts graduate, who grew up around the world.

Kelvin Park’s film portrays South Korean metal shops during the nation’s time

of modern development and Yooah Park’s paintings prod at questions about

“couples,” but juxtaposed with the propaganda posters, all of their differences

melt into a single visual image.

|

| South Korean artist Lee Kakyoung's Window View, 2012 |

The inclusion of

Lee Kakyoung’s video work acts as a humorous visual summary of the almost

deceptive melding of the so-called national and cultural divides within the

entire exhibition. The work, titled Window View, 2012, is the sole piece placed at a narrow wall adjacent

to the monochrome side, only visible when one turns one’s body fully toward the

left-hand side. The sneakiest is the work itself: what appears from a distance

as a slightly open window penciled onto the surface is actually accompanied by

a video projected only onto the open crack of the drawn window. Small people

move around busily outside (inside?) this fictional opening.

The best thing

about the exhibition, though, is that the visual result achieved by the

curatorial efforts overcomes what could have been a cheesy, ideologically propaganda-esque,

and utopia-driven project about a “united” Korea. The simultaneous dissonances

and resonances offered by the visual selection of works in “KOREA” reaches

beyond a singular argument for a possible utopia, but rather opens a dialogue.

During my visit, I overheard other visitors argue whether or not the Kelvin

Park’s film projection was a North Korean film. We need fresh eyes to look at

our world anew in order to change it for the better. I received some hope today

that it may still be possible with art.

No comments:

Post a Comment