|

| View of hauntteddd!! n huntteddd!! n daunttlesss!! n shuntteddd!!, 2013 by Charlemagne Palestine. Twelve-channel sound installation on stairwell landings at the Whitney Biennial 2014. |

Some

of the biggest mistakes I’ve seen people make about art are judgments and (more

unfortunately) entire practices based on empty formalism. My observation is

neither a strikingly new revelation nor a particularly contemporary phenomenon,

though many art critics have voiced a deal of dissent against the same ol’ same

ol’-ness of art nowadays. Making such an observation, however, is important

because of how fast information travels now and how “market-oriented” the art

world has become (that is, with a more deceptive semblance of a greater

inclusiveness of those who are allowed to participate in the game vs. the no

non-sense closed-off-ness of monarchical patronage… or something). Because

information travels so fast, formal trends easily bleed into ideological, political,

and other nuanced concerns; monetary value easily becomes confused with

aesthetic, political, philosophical values, and so on. None of these are always

very easily distinguishable from each other, but it is important to make an

effort to see where one aspect might influence the other and why these occur

together now, or then or later, or not at all. It is important to see

critically. Sometimes it is easier to consume simply what is fed to you rather

than question what it is you are being fed—that is why art and cultural critics

are necessary, more than ever now.

Given

the necessity of critical thought in such a fast-paced, info-driven,

instant-gratification consumer-demand-driven world (whew), I always find it

incredibly disappointing—most of the time infuriating—to witness laziness in a

show organized by a major institution. I may not always agree with every aspect

of an exhibition put forth by the big names in NYC, but no matter how boring or

safe I think a show may be, I rarely think they do not deserve their status.

However, I may have experienced my first majorly long lasting feeling of such

profound questioning at this year’s Whitney Biennial. Sorry, but no. No no no.

I

will keep this short and simple: the three main floors of the Biennial were jam-packed

warehouses of a bunch of “contemporary SHIT” through which I had to sort, with

immense effort, so that I could pick out some of the actually good art work. I

am sure not all of it was pure shit, but the curatorial work came off lazy and

offhanded—the installations were not in any of the works’ favor. Throwing

together a bunch of text-based political work in one room (along with maybe 6

other crazy looking STUFF) then a room devoted to Bjarne Melgaard’s godforsaken

cocks and penises (can’t leave that bad boy out of this contemporary biennial,

can you?), maybe some other weird looking new media installations and videos,

recycled ab-ex paintings… Oh and of course throw in some doodles by a dead

(white male, now already legendary, oh he was too young) author—nevermind the

many many living and talented artists devoting their lives to making real art!

|

| View of hauntteddd!! n huntteddd!! n daunttlesss!! n shuntteddd!!, 2013 by Charlemagne Palestine. Twelve-channel sound installation on stairwell landings at the Whitney Biennial 2014. |

The best stuff:

1) Single Stream (2014) by Pawel Wojtasik,

Toby Lee, and Ernst Karel. 23 min single-channel video.

I may be biased—maybe this

has become my new cinematic aesthetic because of A Dream of Iron (2014)—but the

visual experience of this work speaks more than words could every fully

articulate about trash and recycling, waste, labor, and capitalist,

mass-producing, consumerist society. The imagery and sounds are actually quite

beautiful—it opens and (almost) closes with a flurry of “snow” (trash) and a

pretty twinkling of fairy dust sounds (discarded / sorted metal against metal).

The array of colors in an endless stream of WASTE made me hold my breath many

times (the sounds and images are slow-mo in parts), like a flow of rare gems or

ecstatic confetti, all the way down to the blue aluminum of the Bud light

bottles.

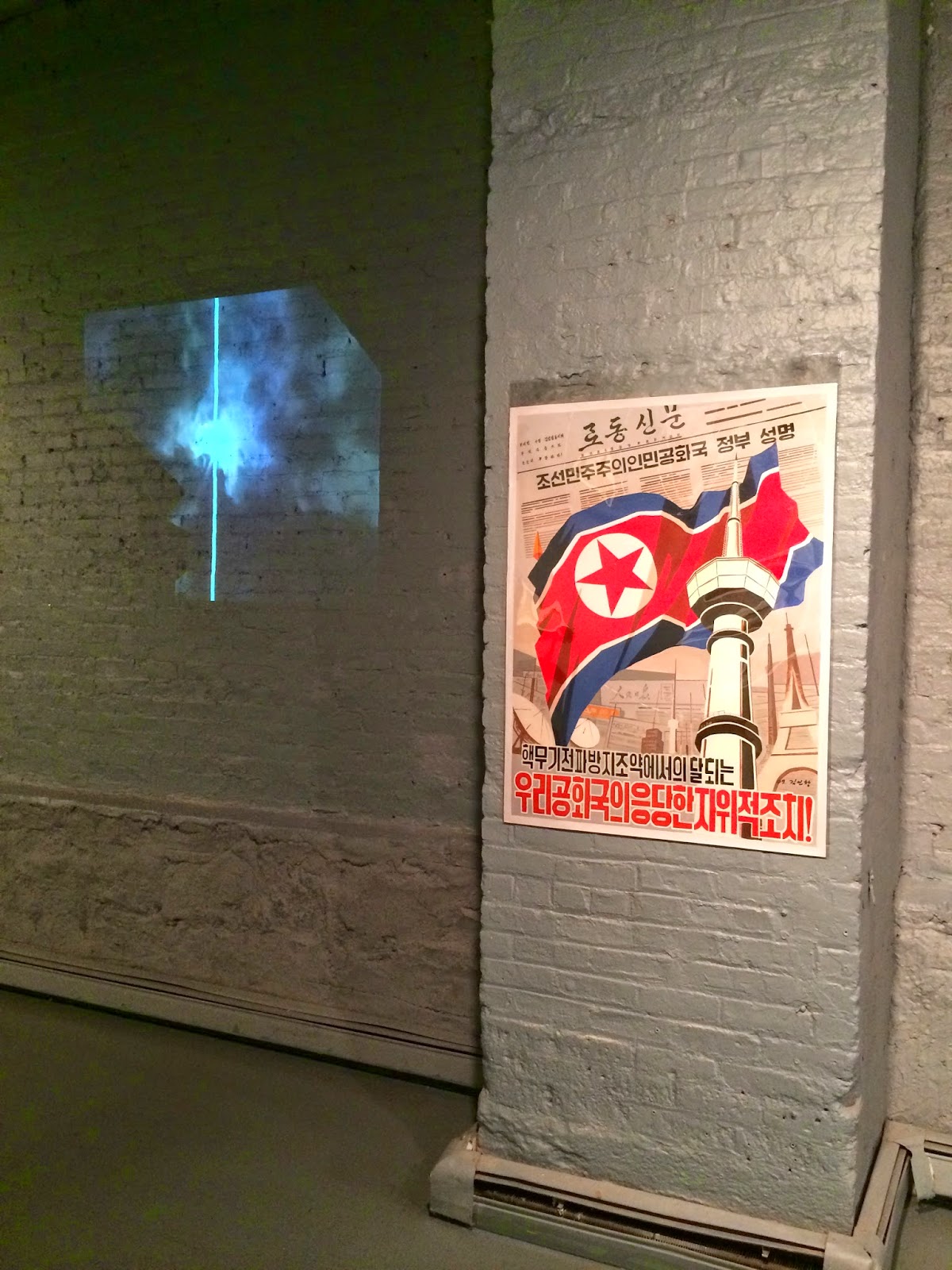

2) Hauntteddd!!! n huntteddd!! n

daunttlesss!! n shuntteddd!!, 2013 by Charlemagne Palestine. Twelve-channel

sound installation on stairwell landings.

Unpretentious, not full of

empty shit. It was what it was and did not pretend to be or to do more. It was

creepy but cute in a humorously angsty contemporary young art kind of

way—walking down the stairs, never-endingly suspenseful old-school horror movie

sounds flowed from the speakers installed at every landing, fully decked with

its own entourage of stuffed animal/characters—some were Mickey, Hello Kitties,

anonymous monkeys and long bits of colorful fabric allowed to hang from the

gatherings. The creepy fun-house aspect kept it simple (I think), and the work

provided nice breaks from the insane warehouse experience of every floor.

Honorable mention: Untitled (I Was Looking Back To See If You Were Looking Back At Me To

See Me Looking Back At You), 2014 by Michel Auder. Three-channel video

installation, 15:12 mins.

A

nice experiential rendering of NYC—slow setting moon, visible behind buildings,

streams of car lights through dark streets, creepy zoom-in shots of undressing

and fucking neighbors. A lot of recognition and familiarity, but too simple?

Maybe I need more time with it.

|

| View of Untitled (I Was Looking Back To See If You Were Looking Back At Me To See Me Looking Back At You), 2014 by Michel Auder. Three-channel video installation, 15:12 mins. |

I

have also noticed that the ones I picked out as “the best” were allowed

relatively isolated locales within the otherwise chaotic biennial. The issue

appears to be more of a curatorial one, which is unfortunate, because it throws

potentially good work into a large dump of a whole bunch of SHIT (have I said

that enough times?). Good work definitely got lost from my eyes, which are bad

(deteriorating eye sight, which I often like to moan about) and also impatient

(possibly because they are bad). Whether the problem is my own laziness, I feel

there is a degree of curatorial responsibility which the Biennial’s organizers

failed to uphold—I do not feel very hesitant in questioning the Whitney’s role in

placing value on “good” or “hot” or “notable” contemporary art. If we are going

to include “trends” inevitably as a part of making such value judgments, going

to Volta (or if you want a more bland and established Chelsea route, Armory)

will give you a better look at “crazy” and “new” “investible” art than a

so-called contemporary art museum. If you’re going to go that way, why bother

with a museum? Galleries, art fairs are where the money’s at.

|

| View of Yooah Park's Couples Series Installation at Volta NY 2014. |